Chinese companies are expanding their investment footprint in Southeast Asia (SEA) as they search for lower costs, market diversification, and new growth engines beyond a slowing domestic market. The region has become central to the emerging “China+N” strategy, where firms build multiple overseas bases to spread geopolitical and supply chain risk. SEA’s young demographics, rising GDP, and competitive labor costs make it a natural choice. In 2024, China’s outbound direct investment reached USD 162.8 billion, with investment into ASEAN rising 13 percent year-on-year, far outpacing the global average. Manufacturers make up roughly 40 percent of companies moving operations abroad, and Chinese executives increasingly view ASEAN not just as a backup location but as a primary source of future growth. From electronics to EVs, SEA is seen as an extension of China’s supply chain network, offering proximity, cultural familiarity, and improving infrastructure. In theory, it represents a win-win: diversification for Chinese firms and industrial upgrading for host economies.

In practice, however, several Chinese companies struggle to replicate their domestic success once they begin operating in Southeast Asia. Expansion optimism often collides with strategic misjudgments, regulatory surprises, operational bottlenecks, cultural friction, and reputational challenges. This article examines why supply chain expansion into SEA often underperforms, highlights real examples of both success and failure, and outlines the strategic imperatives Chinese executives must internalize before committing to the region.

The Core Misread: SEA Is Not “Southern China 2.0”

A recurring issue is the assumption that Southeast Asia will resemble the business environment Chinese companies are familiar with at home. Many envision abundant affordable labor, supportive industrial parks, streamlined permitting, and predictable government backing. In reality, the region is far more fragmented and multifaceted. Each country has its own political dynamics, regulatory frameworks, cultural norms, and development constraints.

Chinese executives often discover that the management approach that worked in China does not transfer seamlessly to SEA. Unlike China’s relatively unified regulatory regime and fast administrative processes, SEA presents a patchwork of legal systems, bureaucracies, and political sensitivities. Firms mistakenly assume that local governments will offer China-style preferential treatment or overlook compliance gaps. Instead, SEA governments welcome investment on defined terms, with stricter enforcement and higher scrutiny, particularly for foreign companies with large footprints.

This gap between expectation and reality forms the basis of many strategic, operational, and commercial pitfalls.

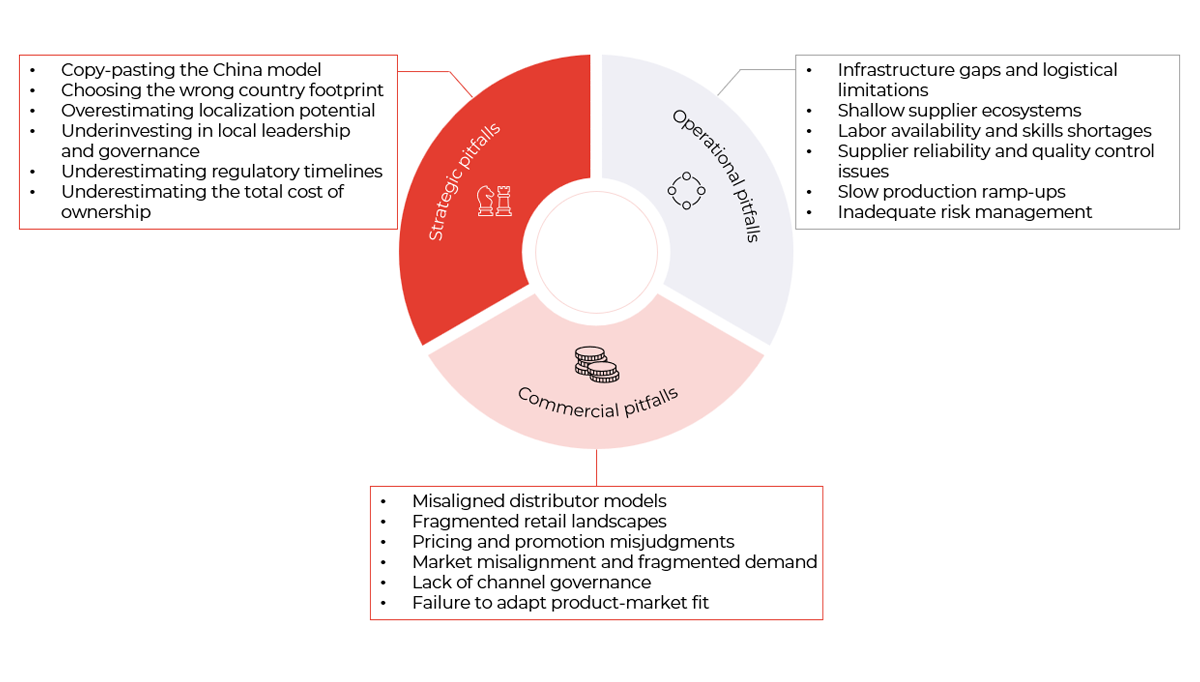

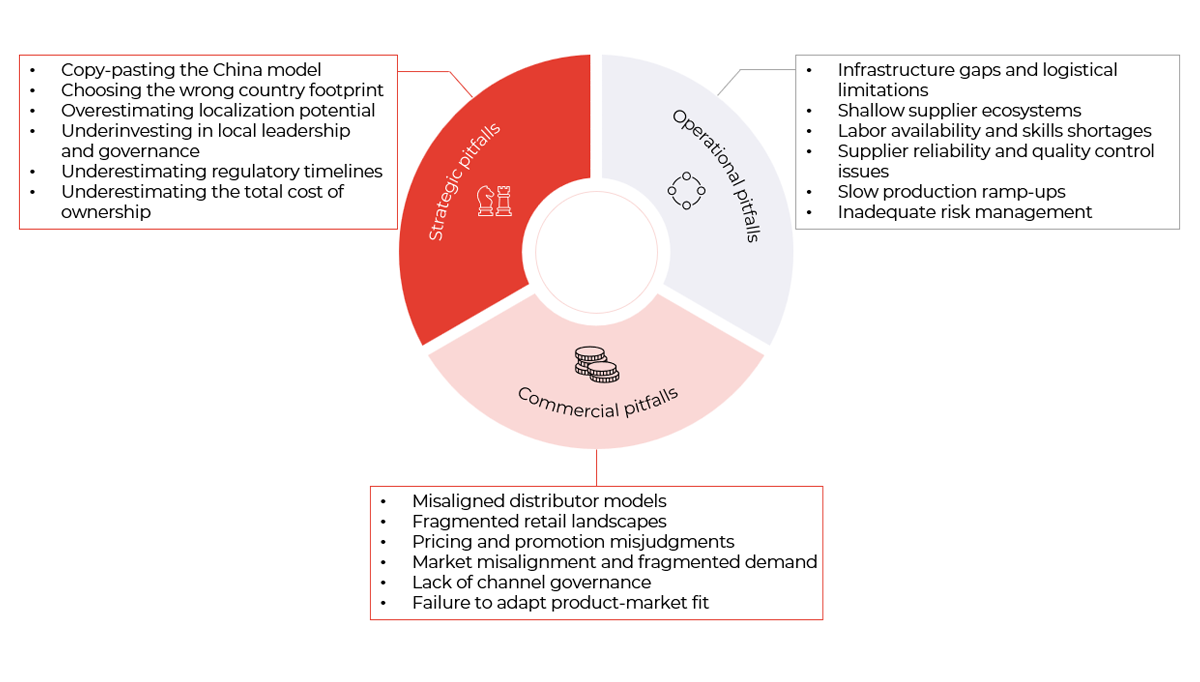

Three Categories of Pitfalls Facing Chinese Firms in SEA

Across countries and industries, most hidden challenges can be grouped into three broad categories including strategic, operational, and commercial & compliance. Understanding these can help companies diagnose where their expansion model is weakest.

1. Strategic Pitfalls

Strategic failures typically come from flawed assumptions and planning. Many firms treat SEA as a single, uniform market or view it as a smaller, slower version of China. This leads to overoptimistic cost projections, unrealistic timelines, and misaligned market entry sequencing. Some select unsuitable entry markets, while others expand into multiple countries before establishing a stable base.

Overdependence on anticipated government incentives is another misstep. Firms often assume tax breaks or subsidies will materialize quickly and smoothly, only to face delays, strict compliance conditions, or changes in political priorities. Regulatory surprises are common: halal certification rules in Indonesia, energy-efficiency labeling in Thailand, country-specific product testing, and new ESG compliance obligations can delay or block launches. Without deep pre-entry scanning of policy landscapes, firms expose themselves to expensive and avoidable mistakes.

2. Operational Pitfalls

Operational challenges emerge once production begins. One of the most common issues is overestimating the maturity of local supply chains. Except for a few advanced clusters, SEA does not yet match China’s dense and highly capable supplier networks. Companies expecting China-like sourcing convenience often confront higher import dependency, longer lead times, and weaker supplier capability.

Talent is another significant constraint. SEA markets face severe shortages of engineers, technicians, and middle managers. Manpower’s 2025 survey indicates approximately 77 percent of Asia-Pacific employers report difficulty finding skilled labor. Combined with different work cultures, this leads to slower productivity ramp-ups, weakened process control, and higher defect rates. New plants often require significantly more time than planned to achieve stable output. The operational reality regularly proves more demanding than Chinese managers anticipate.

3. Commercial & Compliance Pitfalls

On the commercial side, ineffective partner selection remains a common vulnerability. Rushed decisions or reliance on personal networks can lead to choosing distributors or joint venture partners with limited capability or misaligned incentives. Misreading local consumer behavior also undermines performance, especially when pricing, channel design, or marketing strategies are transferred directly from China.

Compliance shortcomings also carry substantial risks. Companies may overlook country-specific certifications, testing requirements, or legal obligations. Non-compliance can result in penalties, loss of incentives, reputational damage, or forced operational restructuring. In markets where transparency and labor protections are high priorities, missteps escalate quickly into public or governmental scrutiny.

Case Studies: Success and Failure in Practice

Success: SAIC–GM–Wuling’s EV Strategy in Indonesia

SAIC–GM–Wuling represents a strong example of Chinese companies’ effective localization in SEA. Rather than depending solely on CKD assembly, Wuling invested in a fully localized EV manufacturing base in Indonesia, integrating production, R&D, and later local battery supply. The company achieved Indonesia’s 40 percent local content requirement, unlocking incentives, and built strategic partnerships with state-owned enterprises on charging networks and talent development. By encouraging key Chinese suppliers like Gotion to co-locate, Wuling established a functional ecosystem around its plant. Strong after-sales service and nationwide dealer coverage helped build trust, enabling Wuling to capture over 37 percent of Indonesia’s EV market and produce more than 40,000 units of the locally assembled Air EV. The case demonstrates that deep localization, compliance discipline, and ecosystem-building translate directly into competitive advantage.

Failure: Hozon Neta’s Setback in Thailand

Hozon’s Neta provides a cautionary counterexample. The company entered Thailand aggressively in 2022, supported by generous EV subsidies contingent on meeting local production commitments. Although Neta initially recorded strong sales exceeding 12,000 units in 2023, it failed to meet its production milestones, making it unlikely to achieve the required 19,000 locally assembled units by end-2025. Its parent company’s financial distress further limited investment. Customers subsequently faced spare-part shortages, service-center closures, and more than 220 official complaints. Sales plummeted, staff and dealerships were cut, and regulators signaled the possible withdrawal of subsidies. Neta’s experience underscores the risks of prioritizing sales growth ahead of building stable operations, financial resilience, and after-sales infrastructure.

Social Backlash: Lessons from Nickel and Apparel

In Indonesia’s nickel industry, several Chinese-backed smelters have faced escalating tension over safety lapses, wage disparities, and insufficient engagement with local workers. At the GNI smelter in Sulawesi, unresolved grievances culminated in a 2023 incident that resulted in fatalities and significant property damage. Government intervention followed, highlighting how labor issues can rapidly escalate into national policy scrutiny.

In Cambodia’s garment sector, a Chinese-owned factory in Kampong Speu faced protests when more than 7,000 workers walked out over punitive rules and excessive unpaid overtime. Authorities intervened, and the company was required to revise its practices. These cases reinforce the importance of labor standards, community engagement, and cultural sensitivity in SEA.

Strategic Imperatives for Chinese Companies Entering SEA

For Chinese industrial and manufacturing firms, the overarching message is clear: success in SEA requires a fundamentally different approach from success in China. High-performing companies localize their operations, invest in talent, and build supplier ecosystems, rather than running SEA subsidiaries as extensions of a China-centric model.

Key imperatives include:

- Conduct deep market and regulatory research to avoid misinterpretation and unforeseen constraints.

- Customize strategy for each country, recognizing their political, cultural, and regulatory differences.

- Invest early in local talent development, empower local management teams, and reduce reliance on expatriate-heavy structures.

- Build strong compliance foundations, securing permits, understanding incentive conditions, and preparing ESG and regulatory plans in advance.

- Engage proactively with governments, communities, and workers, demonstrating transparency and long-term commitment.

- Adopt a patient, incremental view of success, avoiding China-based expectations of scale or speed.

As one experienced advisor remarked, companies must sometimes “unlearn the China success narrative” because evaluating SEA through a China lens leads to disappointment and frustration. SEA requires humility, patience, and genuine willingness to adapt.

The good news is that the opportunities are substantial. A booming consumer base, strategic geography, and growing manufacturing ecosystems make Southeast Asia one of the most attractive destinations for Chinese supply chain expansion. With careful planning, localized execution, and a long-term mindset, Chinese firms can turn the region’s complexity into lasting competitive advantage.

Ultimately, the lessons from Chinese expansions in Southeast Asia are clear. Regulatory hurdles, operational gaps, and cultural blind spots are not isolated events but symptoms of deeper strategic and commercial misalignments. The contrasting outcomes of Wuling and Neta show success in SEA is determined not by investment scale but by localization depth, compliance discipline, and early investment in people, partners, and after-sales capability. SEA is not a low-cost extension of China but a distinct region where companies must adapt to local rules and expectations. Companies that enter with preparation and long-term commitment will outperform, while those that underestimate the region will continue to face setbacks.

Author:

Kelly Nguyen

Associate

Author:

Clyde Tran

Analyst