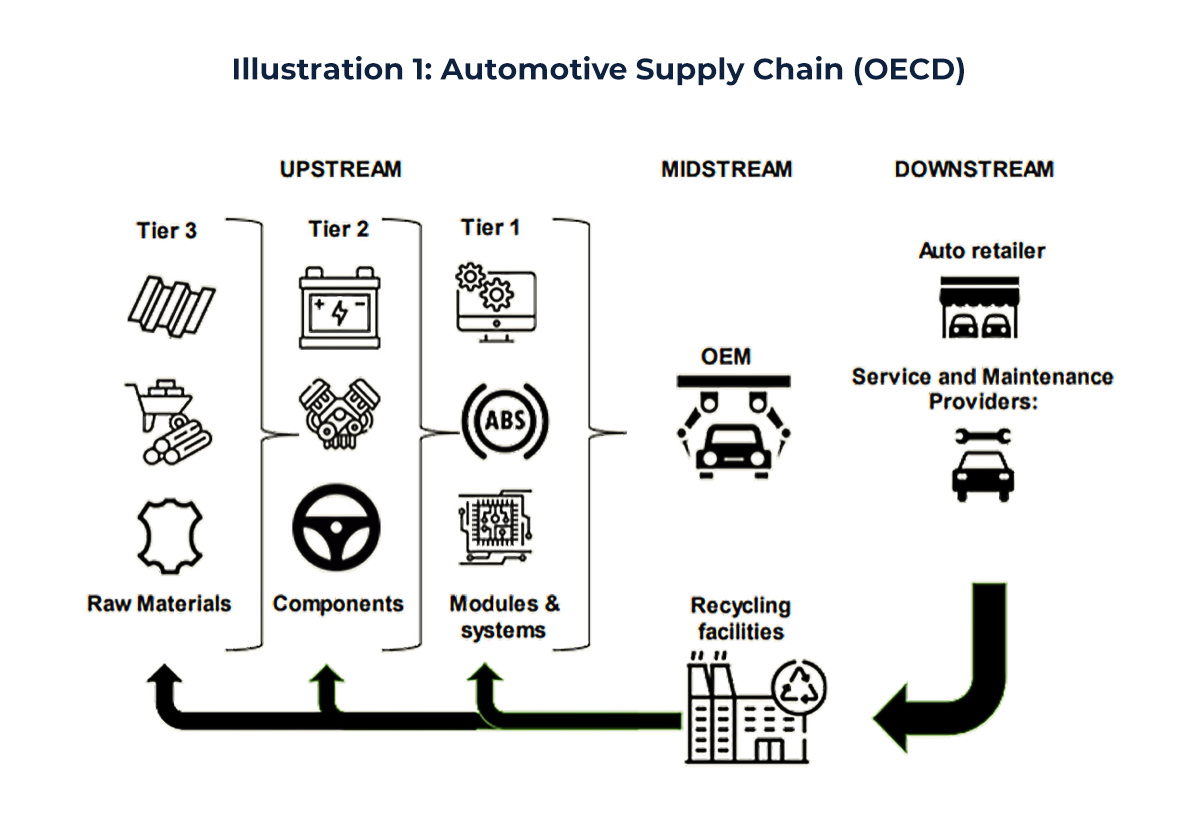

I. Overview of the Mobility Sector Value Chain

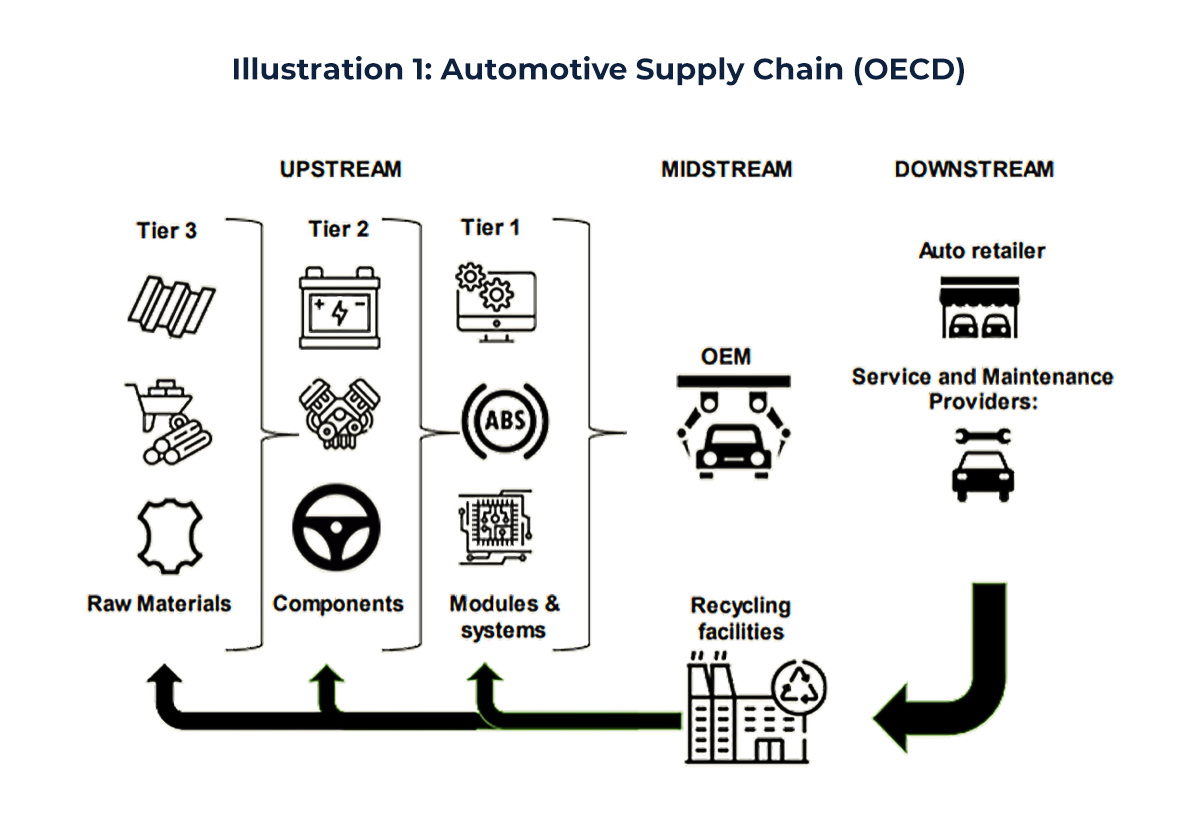

The automotive mobility sector encompasses a long and complex value chain – from raw materials all the way to end-of-life recycling.

- At the upstream end, Tier 3 material suppliers provide basic raw materials (metals, polymers, battery minerals, etc.), and Tier 2 component manufacturers produce parts and sub-assemblies. Next, Tier 1 suppliers deliver major systems (engines, e-motors, transmissions, electronics, software) directly for vehicle assembly.

- In the midstream, automaker OEMs handle the design, manufacturing, and assembly of vehicles.

- Downstream, the value chain extends through distribution networks (importers, dealerships) and after-sales services (maintenance, parts, charging infrastructure, etc.) to the final users. In recent years, new layers have been added – for example, battery gigafactories and software platforms are now critical links, and recycling & circular economy initiatives are emerging to reclaim materials and remanufacture components at end-of-life.

This value chain is not only extensive but also economically vital. The automotive industry remains a key sector in many economies, contributing significantly to manufacturing value-add, employment, innovation, and exports. It is also highly globalized: production and supply networks span continents, and over the past 25 years global output has shifted geographically. Notably, China has emerged as the world’s largest auto producer, accounting for about 32% of global automobile production in 2022. Traditional hubs like Europe have seen their share decline (EU manufacturers produced roughly 15% of global vehicles in 2022). Meanwhile, regional production clusters have solidified – for instance, around Germany in Europe, around the US in the Americas, and around China (and Japan) in Asia. This globalization means that the supply chain for any given vehicle is truly international: a European car may contain battery cells from Korea, semiconductors from Taiwan, wiring harnesses from North Africa, and software from California, assembled together in a German factory. Such interdependence also exposes the sector to global shocks – recent crises like the pandemic, war in Ukraine, and US-China tensions have prompted firms to reassess and “reshuffle” supply chains at all stages, from sourcing of materials to distribution.

II. Key Trends Shaping Mobility Supply Chains

Several powerful trends are transforming the industrial and mobility supply chain landscape, creating both challenges and M&A opportunities:

1. Electrification and Technological Shift

1. Electrification and Technological Shift

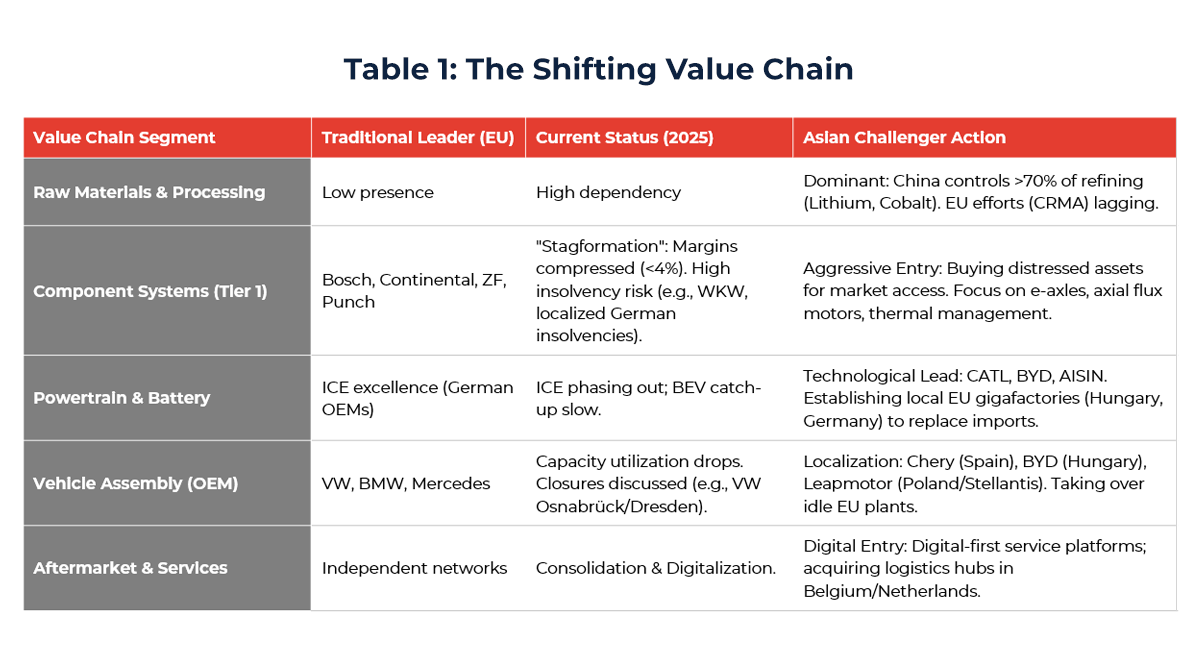

The automotive value chain is shifting towards electric, connected, and autonomous vehicles, disrupting long-established industry structure. Electric vehicles (EVs) require new core components (high-voltage batteries, e-motors, power electronics) while traditional parts like combustion engines and multi-gear transmissions diminish in importance. This has set off a race for battery technology, powertrain software, and semiconductor supply. Legacy suppliers focused on combustion-era technologies face pressure to pivot or consolidate. At the same time, automakers are investing heavily in software and digital services (“servitisation”) to add value beyond the hardware. The net effect is a significant reallocation of value within the chain – for example, batteries can represent 30-40% of an EV’s cost, funnelling revenue toward battery cell and materials suppliers. Many incumbent suppliers are struggling to keep up with the rapid pace of innovation required (from advanced driver assistance systems to AI software), which in turn is prompting partnerships, acquisitions, or exits. Indeed, OEMs have increasingly turned to acquisitions or alliances to obtain cutting-edge tech (for instance, in autonomous driving and software) rather than developing everything in-house, in order to shorten time-to-market. The transformative impact of electrification is evident in Europe’s supplier base: the pivot away from combustion has contributed to a series of restructuring moves – even top-tier suppliers (ZF, Bosch, Webasto, to name a few) have recently announced job cuts or reorganization, underscoring the structural challenges faced in the EV transition.

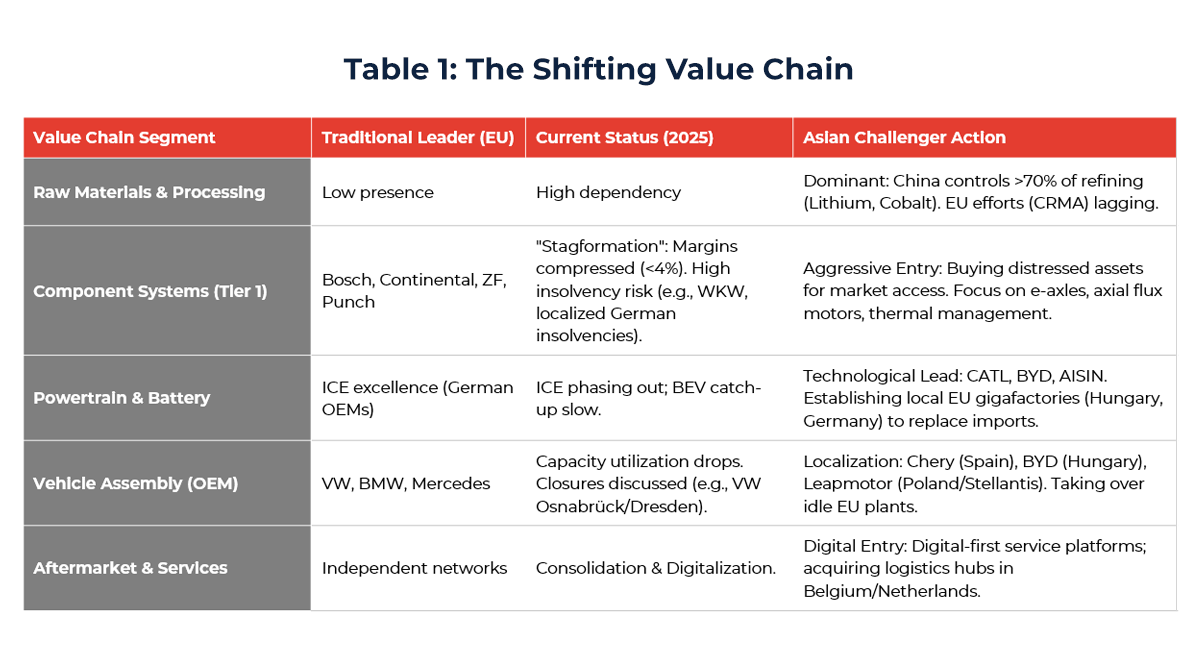

2. Rise of Asian Players and Outbound Expansion

Asian firms – especially from China – have dramatically increased their weight in the global automotive supply chain. A decade ago, Chinese suppliers were marginal players internationally; today they are significant competitors across multiple component segments. By 2023, 9 of the world’s top 100 auto parts suppliers were Chinese (up from only 1 in 2012), collectively accounting for over 9% of Top-100 supplier revenue. This share is forecast to expand further, with analysts projecting that by 2030 roughly 17–20 of the top 100 suppliers could be Chinese, including potentially the world’s largest supplier (e.g. CATL in batteries). Chinese companies have built dominant positions in EV batteries and electronics – for example, CATL leads the global battery market, and Chinese firms also lead in areas like tires (e.g. Sailun), interior components, and safety systems. Crucially, China also controls much of the critical raw material processing for the EV transition: it processes a majority of the world’s lithium, cobalt, rare earth metals, and other key minerals used in batteries and electric drivetrains. This domination in upstream materials and battery supply gives Asian (especially Chinese) firms a strategic advantage in the new mobility ecosystem.

Equally noteworthy is the surge in outbound investment by Asian mobility companies. Faced with fierce competition and overcapacity at home, Chinese EV makers and suppliers have turned to global markets at an unprecedented scale. In fact, Chinese automakers’ overseas investment in the EV value chain soared to an average of $30+ billion per year during 2022–2024, up from only ~$8.5 billion annually in 2018–2021. For the first time, in 2024, Chinese auto companies invested more abroad than domestically – a historic pivot driven by saturated home markets and a strategic push to “go global.” This has translated into multiple greenfield projects and acquisitions worldwide. In Europe, Chinese battery and component manufacturers have been aggressively setting up production facilities: e.g. CATL’s €1.8B battery cell plant in Germany (Erfurt) is ramping up to 14 GWh capacity; EVE Energy is investing in a large battery factory in Hungary; and others have built plants for tires, chassis, and drivetrain parts across Eastern Europe. Between 2024 and 2026, Chinese suppliers are slated to open at least 17 new factories in Europe (11 battery gigafactories, 2 powertrain plants, 2 electronics plants, etc.), primarily in EV-related fields. Alongside greenfield investments, Chinese firms have actively pursued M&A – about 40 acquisitions of European automotive suppliers by Chinese companies have occurred in the last five years, giving them quick access to technology, brands, and distribution networks in the West. Prominent examples include Chinese investors taking over Italy’s Pirelli (tires), Germany’s Kiekert (locks), Grammer (seating), and most recently Leoni AG, a major German wire harness manufacturer (case study below). This trend reflects a broader strategy: as Chinese OEMs (like BYD, Geely, SAIC, Chery) expand globally, they are bringing their supply chain with them – either by acquiring established Western suppliers or by transplanting their own supplier operations overseas. The net result is that Asian players are capturing a growing share of the industrial value-add in global automotive production. Western incumbents are increasingly on the back foot, facing cost-competitive and technologically advancing rivals from Asia.

3. Supply Chain Reconfiguration: Resilience, “Friend-Shoring” and Policy Influences

Recent geopolitical tensions and supply disruptions have prompted a strategic reconfiguration of supply chains in the mobility sector. Companies and governments are now more keenly aware of supply chain resilience and national security concerns, especially around critical technologies (batteries, semiconductors) and critical materials. In practice, this has meant new investment patterns: for instance, the United States and Europe have rolled out incentives (the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, EU Important Projects of Common European Interest, etc.) to localize production of EV batteries, chips, and renewable energy components. Major Western OEMs have entered into joint ventures with Asian battery makers to build local gigafactories – dozens of such JV deals have been announced since 2021 (GM with LG Energy; Ford with SK On; Stellantis with Samsung SDI; Volkswagen with Northvolt, etc.). Similarly, carmakers are directly investing upstream to secure raw materials (signing lithium and nickel offtake agreements, investing in mining projects in Australia, Africa, Canada, etc.). These moves are creating new alliance structures up and down the value chain, often blurring traditional industry boundaries (e.g. oil companies like Total and BP investing in battery and charging networks, tech companies partnering on autonomous driving). On the other hand, protectionist currents are also shaping strategy: for example, the European Union launched an anti-subsidy inquiry into Chinese EV imports in 2023, considering tariffs to shield European manufacturers. In response, China warned its automakers to reconsider investments in certain EU countries that back such tariffs. These political dynamics can influence where companies choose to build factories or acquire targets (Chinese firms have favored investment in “welcoming” jurisdictions in Eastern Europe, for instance, while pausing projects in markets perceived as hostile). Overall, the supply chain is becoming more regionally focused (“friend-shoring”), yet the interdependence remains high – complete decoupling is unrealistic in the short term given Asia’s lead in numerous sub-components (as one industry analysis noted, “there is no realistic way to avoid sourcing commodity components from China” in today’s auto industry). Thus, we see a mix of collaboration and competition: Western governments seek to foster local champions, but Western firms also recognize the need to partner with Asian technology leaders to stay competitive. This tension itself is driving M&A and joint ventures as firms jockey to position themselves in an evolving global supply network.

4. Consolidation and Investment Opportunities

The rapid shifts in the mobility landscape have created pockets of financial stress as well as strategic opportunity. On one side, several legacy suppliers in Europe are financially strained – especially those mid-sized firms caught by the double impact of electrification (requiring new investment while legacy revenues decline) and global price competition. Some have undergone restructurings or asset sales, making them potential acquisition targets for investors or overseas competitors. A striking recent example was Sweden’s battery startup Northvolt – once a symbol of Europe’s EV ambitions – which had to suspend expansion plans and even filed for U.S. Chapter 11 protection for one unit in late 2024, amid sluggish EV demand and intense Chinese competition in the battery sector. Similarly, numerous Tier-2 and Tier-3 suppliers across Germany and elsewhere are up for sale or seeking capital injections. This presents M&A opportunities for those looking to acquire valuable industrial know-how or manufacturing capacity at a discount. Many Asian companies (and some private equity funds) see an opening to pick up advanced engineering companies, established brands, or even distressed OEM assets in Western markets. On the other side, cash-rich automakers and suppliers are using M&A offensively to realign their portfolios – shedding non-core divisions and buying into high-growth areas. For instance, we have seen global automakers divesting legacy fuel-engine businesses (often carving them out into new joint ventures) while investing in e-mobility and software companies. The Renault–Geely powertrain joint venture in 2023, which merged their combustion-engine divisions to free up resources for EVs, is a case in point. Overall, the pace of deal-making in the auto-tech space has accelerated: the OECD reports that automotive-sector M&A activity has grown significantly over the past decade, especially acquisitions targeting tech firms in areas like autonomy and electrification.

All these forces suggest that consolidation is not a crisis but rather an opportunity: a chance for new investors to step in with fresh capital, for stronger players to acquire innovative startups or distressed rivals, and for cross-border partnerships to reshape the industry. Below, we highlight two recent case studies that exemplify these trends – one involving an Asian company investing in a European industrial supplier, and another involving a Western OEM partnering with Asian EV technology.

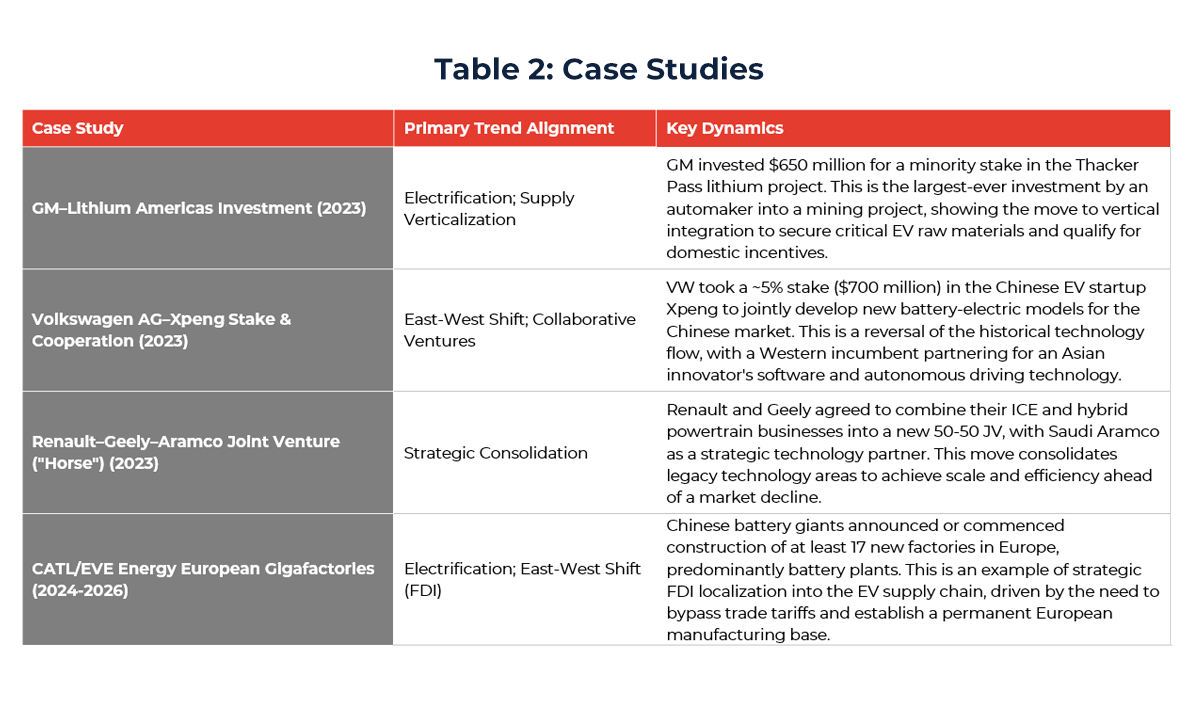

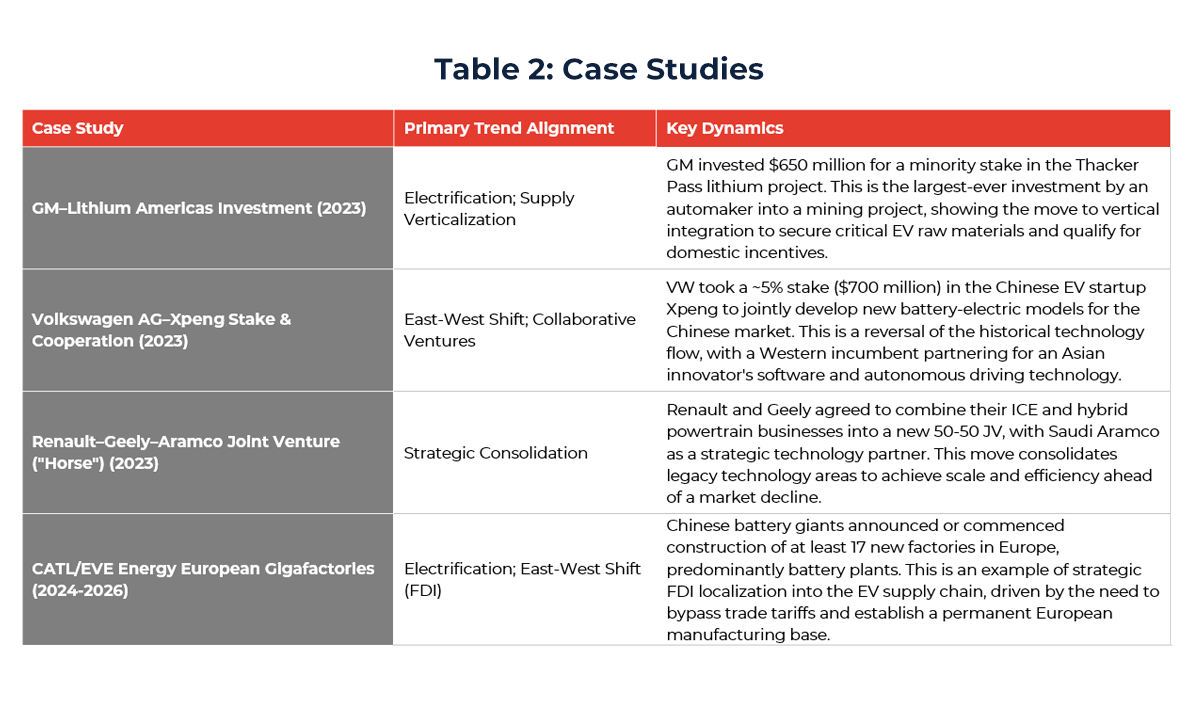

III. Deep Dive Case Studies (2023–2025)

Case Study 1: Chinese Investment Revives a German Supplier (Luxshare–Leoni)

One notable deal was the acquisition of a majority stake in Leoni AG by China’s Luxshare. Leoni, a 100-year-old German automotive supplier specializing in wiring harnesses and cable systems, had been struggling financially during the EV transition. After a failed divestiture of its cable division pushed it into distress, Leoni underwent a major restructuring in 2023 and was taken private by an investor. In September 2024, Luxshare ICT – a Chinese electronics and automotive components group – agreed to buy 50.1% of Leoni and effectively assume control. The transaction, completed in 2025 after regulatory approvals, valued the controlling stake at approximately €320 million. Luxshare also acquired Leoni’s Automotive Cable Solutions unit (through a subsidiary) as part of the deal.

Strategic rationale:

This partnership marries Leoni’s entrenched position as a wiring supplier to virtually all the major Western automakers with Luxshare’s strengths in electronics and connections to the booming Chinese EV sector. Leoni brings a long-standing OEM customer base and deep engineering expertise, while Luxshare provides financial strength and access to high-growth EV manufacturers (Luxshare is a supplier to Tesla in China and to several Chinese automakers). The companies noted that as Chinese electric vehicle OEMs expand into Europe and North America, Leoni (under Luxshare’s ownership) will be well-positioned as a “trusted partner” to support those new entrants with advanced wiring systems. In other words, the deal gives Luxshare a respected platform in Europe, and it secures Leoni’s future by integrating it into a global supply chain oriented toward EVs. Leoni’s CEO hailed the investment as “enhancing Leoni’s competitiveness across all fronts,” while Luxshare’s CEO described it as a “pivotal step” toward becoming a global automotive leader. Notably, Leoni’s situation also reflects the broader pressures on EU suppliers: the German auto industry is grappling with the move from combustion engines to electric, and competition from Asia is intensifying. A number of European suppliers have faced profitability issues, prompting consolidation moves like this. For Luxshare, acquiring Leoni provides not only technology and R&D talent but also immediate relationships with Western automakers – something that might have taken years to build organically. In sum, this case demonstrates how Asian investors are capitalizing on Europe’s industrial openings, injecting capital into underperforming firms and aligning them with the new growth areas of mobility. It’s an example of a win-win: Leoni’s turnaround is secured and its ~95,000 jobs stabilized, while Luxshare gains a foothold to serve the wire-harness needs of EV makers globally.

Case Study 2: Western OEM Partners with Chinese EV Innovator (Stellantis–Leapmotor)

While Chinese firms have been buying into Europe, we also see Western companies looking East for technology. In October 2023, Stellantis N.V. (the Europe-U.S. auto group behind Peugeot, Fiat, Jeep, etc.) announced a strategic partnership with China’s Leapmotor, a young electric vehicle manufacturer. Stellantis agreed to invest approximately €1.5 billion for a 21% stake in Zhejiang Leapmotor Technologies – marking one of the largest foreign investments in a Chinese EV firm to date. As part of the deal, the companies are forming a new joint venture (Stellantis 51%, Leapmotor 49%) that will have exclusive rights to export and sell Leapmotor’s EV products outside China. In essence, Stellantis gains access to Leapmotor’s advanced EV platform and technology, and in return Leapmotor gets a pathway to expand into international markets via Stellantis’ global distribution network.

Strategic rationale:

For Stellantis, this move is about catching up in electric tech and re-establishing a foothold in China – the world’s largest auto market and the epicenter of EV innovation. Like other legacy automakers, Stellantis had been “playing catch-up” in the EV race, and its sales in China were lackluster. By partnering with Leapmotor, Stellantis immediately taps into a pipeline of competitive EV models and underlying technology (batteries, electronics, software) developed in China’s high-pressure market. Stellantis’ CEO Carlos Tavares was blunt about the rationale: “The Chinese offensive is visible everywhere… With this deal we can benefit from it rather than being the victims of it.” In other words, rather than simply worry about Chinese EVs undercutting Peugeot or Fiat in Europe, Stellantis decided to ally with a Chinese player and share in the growth and cost advantages Chinese firms have achieved. Analysts noted that China is at the forefront of EV technology and enjoys a huge cost advantage, so this stake gives Stellantis a relatively affordable way to acquire cutting-edge know-how (a “de-risking” step, as one analyst called it). For Leapmotor, a smaller EV maker amid dozens of Chinese competitors, Stellantis’ investment is a major validation and provides capital and global reach. The joint venture will allow Leapmotor-designed vehicles to be manufactured and sold overseas – effectively giving the Chinese brand a European/American market entry with the backing of an established player. This case exemplifies a trend of new cross-border alliances: it followed on the heels of a similar partnership in July 2023, when Volkswagen invested $700 million for a 4.99% stake in China’s XPeng and agreed to co-develop EVs on XPeng’s software platform. These alliances “herald a new era” of cooperation, reflecting China’s rise as a global center of EV technology and the recognition by Western OEMs that they must integrate some of that Chinese innovation to remain competitive. The Stellantis-Leapmotor deal, once approved by regulators (Chinese authorities greenlit it in 2024), could become a blueprint for other automakers seeking similar tech partnerships. It’s a reminder that in the global supply chain, knowledge flows are now a two-way street – no longer just Western tech going east via joint ventures, but also Asian tech coming west via equity tie-ups. From an investment banking perspective, we can expect more such minority stake investments, joint ventures, and licensing deals as the industry’s incumbents and insurgents form an increasingly interdependent ecosystem.

Other notable cases include: IV. Conclusion and Outlook

IV. Conclusion and Outlook

The intersection of global supply chains and M&A in the industrial mobility sector is creating a dynamic deal landscape. The overarching narrative is one of realignment: the shift to electric and connected vehicles is reshuffling the value chain positions of companies and even entire regions. This realignment produces clear opportunities for strategic M&A and investments. Cash-rich players (whether large OEMs or new entrants) can acquire distressed but technologically rich suppliers to bolster their capabilities. Likewise, companies that find themselves lagging in a critical area (battery tech, software, AI, etc.) may seek mergers or partnerships to avoid being left behind. Geographically, we see capital flowing from Asia into Europe to seize high-value industrial assets, and conversely Western firms investing into Asia (or partnering with Asian firms) to secure innovation and cost advantages. The result is a wave of consolidation that is knitting together a new global supply chain fabric for the EV era.

For clients and investors, several themes emerge: (1) Supply Chain Vertical Integration – Automakers and Tier-1 suppliers are likely to continue upstream acquisitions (mining, materials, battery production) and downstream investments (charging networks, software services) to control more of the value chain and ensure supply security. (2) Cross-Border Tech Synergies – We expect more deals like VW–XPeng or Stellantis–Leapmotor, where East-West partnerships unlock mutual benefits (market access for one side, technology infusion for the other). (3) Restructuring-driven M&A in Europe – Europe’s supplier base, especially in Germany, will continue to consolidate. Some venerable firms will seek buyers due to financial distress or succession issues, and Asian investors (as well as North American and global PE funds) will be keen bidders. The feeling that “European industrial champions are faltering and Asians are buying them out” is now supported by multiple data points – from Chinese firms accounting for 40+ takeovers of European suppliers in recent years, to large investments like Luxshare-Leoni. Rather than being a cause for alarm, this trend can be framed as an inflow of capital and know-how that helps modernize assets and keep them competitive. (4) Policy and Regulatory Backdrop – Deals in this space will face growing government scrutiny (e.g. foreign investment review for Chinese takeovers in the EU, or export controls on sensitive tech). Investors need to navigate these carefully, structuring partnerships or JVs in ways that align with national interests (for instance, by preserving jobs or adding local production). Notably, despite some protectionist headwinds, Chinese investment in Europe’s EV sector jumped 80% in 2024 (to €9.4bn) as per provisional data, underscoring that the momentum of capital flows remains strong.

In summary, the industrial mobility sector is at an inflection point where global supply chain shifts and consolidation are two sides of the same coin. Companies that recognize and act on these trends – through smart M&A, joint ventures, and supply chain realignment – stand to reinforce their positions. For our boutique firm’s clients, especially those in the EU mobility supply chain, staying informed on these global dynamics is critical. There will be opportunities to either find strategic investors from abroad, or to become acquirers of critical technology themselves. The examples of Luxshare-Leoni and Stellantis-Leapmotor illustrate that success will favor the bold and the collaborative. As the value chain continues to evolve toward a cleaner and more digital future, strategic deal-making will be a key lever in building the resilient, globally integrated businesses that can thrive in the new automotive era.

The financial figures and transaction details presented in case studies are derived from publicly available sources, including press releases and media reports. As such, they are intended for illustrative and educational purposes only and may not fully reflect the actual deal structure, terms, or confidential elements of the transaction. Readers should not rely solely on this information for investment, legal, or financial decision-making.

References

1. Electrification and Technological Shift

1. Electrification and Technological Shift