Mid-market mergers and acquisitions, typically involving enterprises valued between USD 50 million and 500 million, constitute one of the most active yet least standardized segments of global deal-making. These businesses occupy a unique position in the corporate landscape: they are no longer small owner-managed enterprises, but they are also not fully mature corporates with the governance and systems associated with large-cap organisations. This in-between status creates a distinctive set of transaction dynamics, where deal structure and execution risk all carry disproportionate weight compared with deals at other ends of the spectrum. Understanding how to navigate these dynamics is essential for both founders and investors.

Mid-market companies generally exhibit proven commercial viability, credible revenue traction, and early organisational depth. Their product-market fit is established, customer pipelines are identifiable, and profitability is often consistent enough to support structured growth. However, they also tend to retain strong founder influence with incomplete institutionalisation. Many companies in this range have management teams that are capable but still dependent on the founder’s strategic direction, and reporting frameworks that lack the rigour of larger firms. This combination creates significant opportunities for investors seeking scalable assets, but it also introduces complexities around diligence and post-transaction integration.

What differentiates mid-market deals from small-cap transactions is the level of sophistication required. While small-cap acquisitions often resemble asset purchases or simple owner-operator handovers, mid-market deals require structured valuation approaches and careful attention to leadership continuity. Conversely, mid-market transactions also diverge from large-cap M&A, where audited financials, well-established governance structures, and experienced management teams allow for a smoother transaction. In the mid-market, data quality varies, the founder’s role is central, and cultural alignment often matters as much as financial return. As a result, deal structuring becomes the primary tool through which incentives are aligned and long-term value is protected.

Common Pitfalls & Misalignments

Both founders and investors frequently encounter misalignments arising from differing priorities. Founders often focus on the headline valuation and the psychological impact of the number, whereas investors concentrate on the quality and sustainability of the underlying cash flows. This distinction explains why earn-outs, rollover equity, and other unique structures are used more commonly in the mid-market than in either small-cap or large-cap transactions. Founders may underestimate the documentation required to support financial claims and the depth of operational scrutiny. Investors, meanwhile, may underestimate how much of the business’s performance depends on the founder’s presence, unique relationships, or informal decision-making processes. These structural frictions explain why well-intentioned mid-market deals often stall or collapse despite strong initial interest on both sides.

Preparing for M&A

1. Establishing the Transaction Framework

Preparing for a transaction begins long before aa investor is identified. Founders first need clarity on the type of deal they intend to pursue, including whether the transaction will take the form of a share sale or an asset sale, how much equity will be made available, and whether minority shareholders will participate. These decisions influence everything that follows, from regulatory requirements to tax treatment and the scope of diligence an investor will perform. A share sale transfers the entire corporate entity, along with its history and obligations, whereas an asset sale allows an investor to acquire selected components. Understanding which structure is appropriate – and ensuring alignment among shareholders early – helps avoid friction once negotiations begin.

2. Pricing Approach and Valuation Expectations

Establishing realistic pricing expectations is another essential early step. Mid-market investors typically anchor valuation on EBITDA and revenue multiples through cash-flow analysis, adjusting for factors such as working-capital requirements, customer concentration, and capital expenditure needs. Founders who understand how these adjustments work are better prepared to frame their financial story, support their valuation expectations, and avoid misunderstandings that can derail the process.

3. Institutional Readiness and Operational Preparation

Operational and institutional readiness remains one of the most important determinants of deal success. For founders, institutionalisation is the most reliable driver of improved valuation and smoother execution. This includes elevating financial reporting beyond basic bookkeeping, adopting accrual-based accounting, separating personal and corporate expenses, and presenting a clean reconciliation of historical EBITDA with adjustments for extraordinary or non-recurring items. It also requires documenting organisational processes, clarifying the responsibilities of senior leaders, and reducing over-dependence on the founder for technical, commercial, or operational decisions. Implementing basic management information systems or establishing consistent monthly reporting routines can materially increase investor confidence and shorten diligence timelines.

4. Materials and Information Preparation

Before engaging advisors or speaking with investors, founders should ensure that the company’s core information is accurate, complete, and easy to access. The most important starting point is clean financials: consistent monthly statements, clear revenue and margin breakdowns, transparent cost structures, and a simple explanation of the key drivers behind performance. Investors place significant weight on the quality of financial reporting, and organised, reliable numbers reduce early concerns. Founders should also prepare the operational and commercial information investors routinely request, such as major customer and supplier summaries, key contracts, product or service descriptions, HR and payroll basics, tax filings, and any relevant licences or compliance documents. These materials form much of what will later appear on an Information Request List (IRL), and preparing them early helps avoid delays or last-minute gaps during diligence. Finally, founders should be ready to explain the business clearly: how it makes money, what drives growth, and where opportunities lie. A simple, evidence-based narrative, supported by data already tracked internally -helps establish credibility and makes the formal sale process smoother once advisors become involved.

5. Communicating Exit Rationale and Investor Fit

Founders should reflect honestly and be able to clearly explain why they are considering a transaction, as this reasoning ultimately shapes how the company will be positioned once the process begins. Whether the motivation is succession, partial liquidity, bringing in a strategic partner, or accelerating growth, having a consistent and credible rationale helps ensure the story resonates with potential investors. Founders should also think through what type of investor is the best fit – such as a global strategic, a regional industry player, or a financial sponsor – since different investor groups bring different capabilities, investment horizons, and expectations. Clarifying these points early helps guide the eventual outreach strategy and ensures that the process aligns with the founder’s long-term objectives.

6. Shareholder Alignment

Internal alignment among shareholders is essential before entering the market, as differing expectations are one of the most common reasons mid-market deals stall. Founders should ensure shareholders agree on whether to sell, how much equity to make available, and the terms they are prepared to accept, including valuation expectations and their willingness to roll over equity. At the same time, shareholders should also align on the overall process design: whether the sale will be conducted through a competitive auction or a bilateral negotiation, the timing and structure of management presentations, and what a realistic timeline to signing looks like. Agreeing on these elements early prevents disagreements from emerging during critical stages such as exclusivity and provides the financial advisor with a clear mandate. A unified internal position not only signals stability to investors but also strengthens the founder’s negotiating posture once the process is live.

7. Cross-Border Planning

Where international investors or multi-jurisdiction operations are involved, founders should work closely with their financial advisor and legal counsel to understand whether the transaction will trigger foreign-investment filings, sector-specific approvals, foreign-shareholding limitations, or antitrust reviews. These regulatory considerations can materially affect deal structure and timing and identifying them early with the guidance of advisors ensures they are incorporated into the process plan rather than becoming last-minute obstacles.

Deal Structures & Case Examples

Deal structuring is where the interests of founders and investors converge or diverge most acutely. Several structural tools are commonly used in mid-market transactions to balance risk and reward.

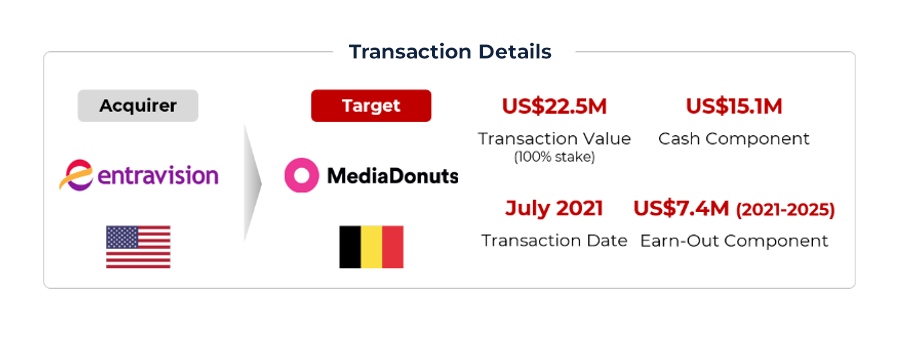

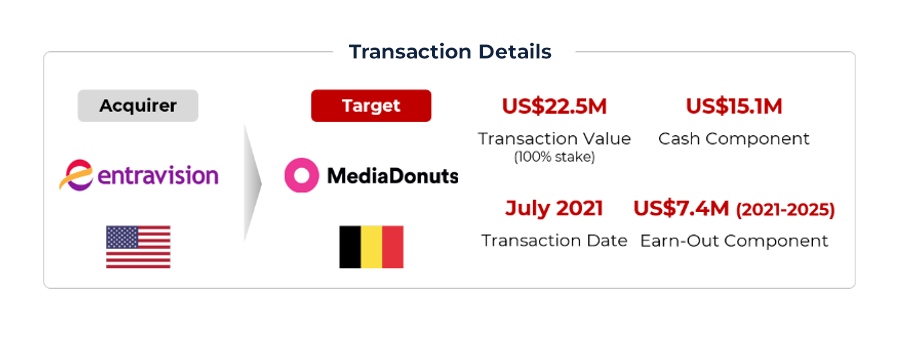

1. Earn-Out

One of the most frequently used mid-market mechanisms is the earn-out. In essence, an earn-out links a portion of the seller’s proceeds to the company’s subsequent performance, allowing the investors to guard against optimistic projections while giving the founder a path to realise a valuation that reflects long-term potential rather than solely historical results. Because performance thresholds often rely on EBITDA or margin expansion, earn-outs can be effective in situations where the business appears poised for growth but lacks the track record to justify a full cash payment upfront. They do, however, require the founder to remain engaged post-closing and introduce sensitivity to how the business is managed under new ownership. A recent example is Entravision’s 2021 acquisition of MediaDonuts, a Southeast Asian digital marketing business that was growing quickly but showed uneven year-to-year results. To balance the founder’s confidence in future performance with the investor’s concerns about volatility, a significant portion of the consideration was structured as a four-year earn-out tied to annual EBITDA. The earn-out was designed so that the founders received additional payments only if the business continued to expand, with higher payouts triggered by stronger EBITDA growth and lower payouts if performance softened. This approach gave the founders the opportunity to realise the valuation they believed was achievable, while giving the investor downside protection if the momentum did not carry through. It is a clear example of how earn-outs can turn differing views of the future into a mutually workable structure.

2. Deferred Consideration

Deferred consideration serves a different purpose. Rather than linking payment to future performance, it simply delays part of the purchase price, so the investor does not need to fund the entire amount at closing. This is commonly used when the investor needs short-term liquidity for post-transaction investment or when the timing of their financing does not perfectly align with the closing date. It can also be a practical compromise when the investor wants some downside protection, but the situation does not justify a full earn-out. For the seller, deferred consideration is more predictable than a performance-based structure because the amount is fixed, although it does require confidence that the investor will remain financially able to make the payments when they come due.

3. Rollover Equity

Rollover equity plays a similarly important role, particularly in businesses where leadership continuity contributes heavily to investor confidence. In a rollover, the seller receives part of the consideration in equity of the post-transaction company or the acquisition vehicle. This keeps key individuals invested in the outcome and preserves stability during the early years of institutional ownership. Founders often find rollover equity attractive because it creates a second liquidity event if the investor exits, while also ensuring that their expertise and relationships remain valued components of the growth plan. In larger public transactions, the same principle applies. When Cascade Investment, Bill Gates’s investment vehicle, joined Blackstone and GIP in the take-private of Signature Aviation, it did not simply tender its shares for cash. Instead, Cascade rolled its existing ~19% stake in Signature Aviation into the newly formed bid vehicle, Brown Bidco, and injected additional equity so that it owned around 30% of the holding company after the transaction. In doing so, it moved from being a public minority in the old, listed entity to a partner in the same holding company as the lead sponsors, with aligned governance and economics. The same structural idea is available to founders in mid-market deals: rather than being left as a residual minority in their old operating company, they can roll part of their stake into the investor’s acquisition vehicle and sit alongside the new investor with clear rights, protections, and a shared exit.

4. Preferred Shares and Convertibles

In some mid-market transactions, especially where investors are taking a minority stake, preferred shares or convertible instruments provide a more nuanced way to balance interests. These structures give investors downside protection and enhanced rights without forcing the founder to relinquish disproportionate control or accept a valuation that fails to reflect the company’s trajectory. Preferred shares typically sit above common equity in the capital structure, meaning investors receive priority if the company underperforms or is sold at a lower valuation. They may also come with fixed dividends, liquidation preferences, or governance rights that allow the investor to protect their position without dictating day-to-day operations. Convertibles begin as debt-like instruments with the option to convert into common equity later, usually at a pre-agreed valuation or discount. This gives investors the comfort of protection today with the potential to participate in upside if the company grows as expected. For founders, these instruments can be attractive because they bring in capital without immediately setting a valuation that feels premature or dilutive, and they avoid surrendering control at a sensitive stage of growth. A contemporary illustration is Google’s multibillion-dollar investment into Anthropic. Instead of purchasing equity outright, Google provided the majority of its funding through convertible notes – debt instruments that offer priority and downside protection but convert into equity upon a major financing event, IPO, or sale. This structure allowed Anthropic to secure substantial capital while preserving governance stability and deferring valuation.

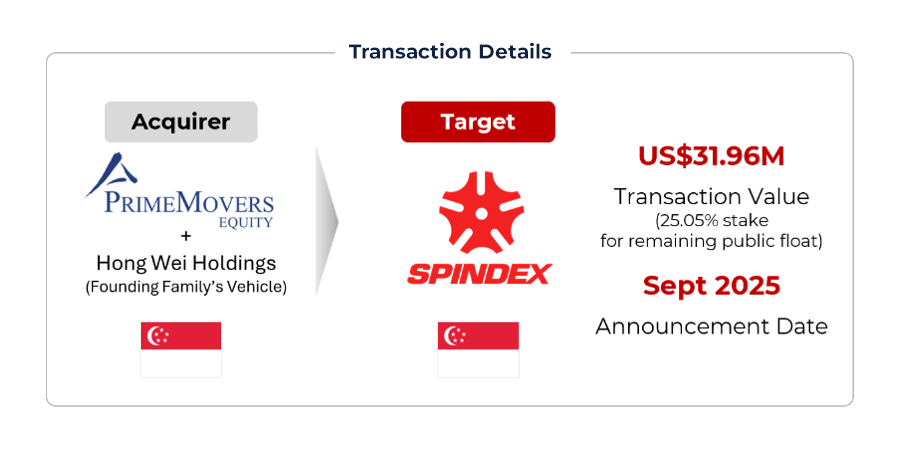

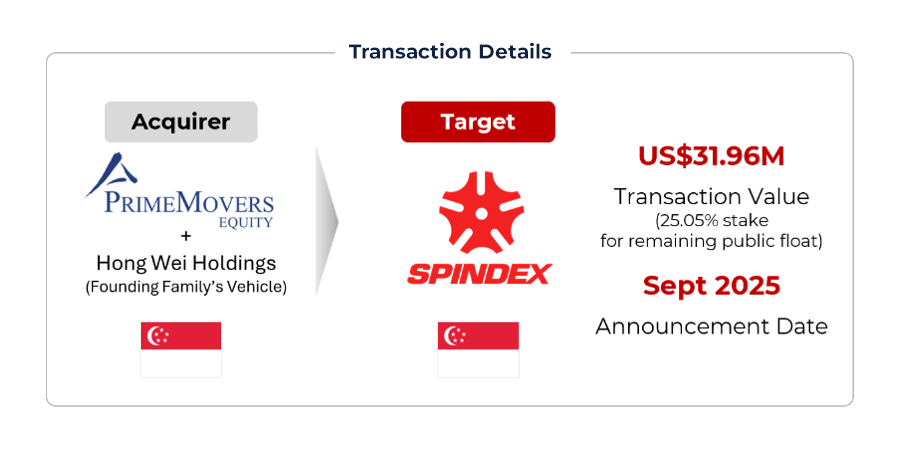

5. Holding Companies & SPVs

Cross-border or multi-subsidiary transactions often introduce another structural dimension: the need to organise ownership through either a special purpose vehicle (SPV) or a holding company. Although the two are sometimes used together, they serve distinct purposes. An SPV is typically created to execute the acquisition itself – a clean, single-purpose entity that isolates risk, supports financing, and keeps the transaction separate from the investor’s existing operations. A holding company, by contrast, is used for the long-term ownership structure: it sits above the operating subsidiaries and consolidates them under one jurisdiction for ongoing governance, reporting, and tax efficiency. These frameworks may appear administrative, but they shape governance, shareholder rights, and the practical experience of holding rollover equity. A clear illustration of this can be seen in the proposed take-private of Spindex Industries by Skyline II, an acquisition SPV backed by a private equity fund and the founding family, with Spindex’s operations spanning Singapore, Malaysia, China, and Vietnam. The investors first incorporated the Singapore special purpose vehicle to house the acquisition financing. Once the transaction completes, the listed company and its operating subsidiaries will sit beneath this acquisition vehicle, which then functions as the holding company for the entire cross-border group. For the founding family, who are partially rolling over their stake, holding equity at the SPV/holding-company level concentrates their rights in a single Singapore entity with predictable governance standards and robust shareholder protections, rather than scattering them across multiple country-level companies. For the financial sponsor, the structure also streamlines future refinancing or exit: selling or recapitalising the holding vehicle effectively transfers control of the whole regional platform without needing to unwind each jurisdiction separately.

Negotiation Dynamics

The negotiation stage of a mid-market transaction is often where founders feel the most pressure, and it helps to understand the levers that typically shape the final outcome. One of the first areas investors will focus on is EBITDA normalisation. Many founder-led companies include personal expenses, related-party items, or discretionary spending in their accounts, and these need to be adjusted so the company’s true operating performance is clearly represented. Another point to prepare for is the working-capital peg. Investors will expect the business to deliver a normal level of working capital at closing, and any shortfall can lead to price adjustments if it is not defined carefully in the agreement. Founders should also pay close attention to what qualifies as “debt” in a debt-free, cash-free structure. Items such as tax exposures, overdue payables, or related-party balances can be interpreted as debt by investors, and clarifying these early avoids last-minute surprises. Finally, if the deal includes an earn-out, founders should ensure that the calculation mechanics cannot be influenced by changes in accounting policy or timing of expenses. Metrics tied to EBITDA or margins tend to be clearer and less prone to dispute than revenue-based targets. Approaching these points with awareness and preparation not only smooths negotiations but also helps founders protect value and maintain momentum through closing.

How Can ARC Group Help?

Mid-market transactions rarely hinge on a single factor. They succeed because the right preparation, information, and judgment come together at the right time.

This is the part of the market where ARC does its best work.

Our role is to help founders organise and present their businesses in a way that stands up to sophisticated diligence. That means working through operational details, cleaning and interpreting financials, clarifying how the company actually generates cash, and preparing management to speak to investors with confidence. These steps reduce uncertainty, shorten the back-and-forth, and allow investors to focus on the fundamentals rather than the noise.

When investors enter the picture, ARC acts as the translator between commercial potential and execution realities. We prepare targeted information memorandums, coordinate investor conversations across regions, and help both sides understand where expectations genuinely align and where they need to be recalibrated. On complex cross-border deals, we also manage the practicalities – regulatory filings, jurisdictional structuring, and the integration of different legal or tax environments – so the process remains controlled rather than reactive. As negotiations progress, we help founders navigate the areas that often determine value: working-capital mechanics, the treatment of related-party items, diligence findings that require explanation, and the parts of the agreement that influence how the business will operate post-closing.

What ultimately distinguishes ARC is not a single strength but the ability to hold all these moving parts together and keep the transaction advancing with momentum and discipline. Mid-market deals stall easily – on valuation pricing gaps, on documentation, on miscommunication – and keeping them alive requires persistent, hands-on involvement.

The mid-market will continue to produce attractive opportunities as companies professionalise and private capital searches for resilient growth. ARC stands in the middle of that intersection: helping founders prepare earlier and more effectively, giving investors the clarity they need to commit, and guiding both sides through a process that is often more intricate than anticipated but far more valuable when executed correctly.

The financial figures and transaction details presented in case studies are derived from publicly available sources, including press releases and media reports. As such, they are intended for illustrative and educational purposes only and may not fully reflect the actual deal structure, terms, or confidential elements of the transaction. Readers should not rely solely on this information for investment, legal, or financial decision-making.

References